Someone You Can Build a Nest In by John Wiswell-Review

The story of a shapeshifting monster who has no humanoid form unless and until she eats enough material that she may construct a body from the inside out. That alone raises some fascinating questions about living in a body and having a gender and more.

Between the incredible artwork n the cover, the title evocative of cozy-home building tropes, and this paragraph, I was sold on John Wiswell's first long-form publication:

Shesheshen has made a mistake fatal to all monsters: she's fallen in love.

Shesheshen is a shapeshifter, who happily resides as an amorphous lump at the bottom of a ruined manor. When her rest is interrupted by hunters intent on murdering her, she constructs a body from the remains f past meals: a metal chain for a backbone, borrowed bones for limbs, and a bear trap as an extra mouth

And then, it turns out, the whole story is sold as a Sapphic romance? Someone You Can Build A Nest In is the story of a shapeshifting monster who has no humanoid form unless and until she eats enough material that she may construct a body from the inside out. That alone raises some fascinating questions about living in a body and having a gender, to say nothing of the disability lens through which Shesheshen is clearly also constructed.

There are a few layers to the narrative that I find compelling. On the surface, this is a fairly straight-forward fantasy novel about finding yourself and finding love, and I've seen more than one reference to the narrative as "cozy" despite the vast amount of body horror and gore present. However, because most of that gore is presented through the idea of Shesheshen's need for survival juxtaposed with significant misunderstandings between monsters and humans, the effect is one of absurdity rather than disgust. Shesheshen's body cannot do the things humans can do unless she literally ingests bones and other organs to craft assistive devices out of her own body.

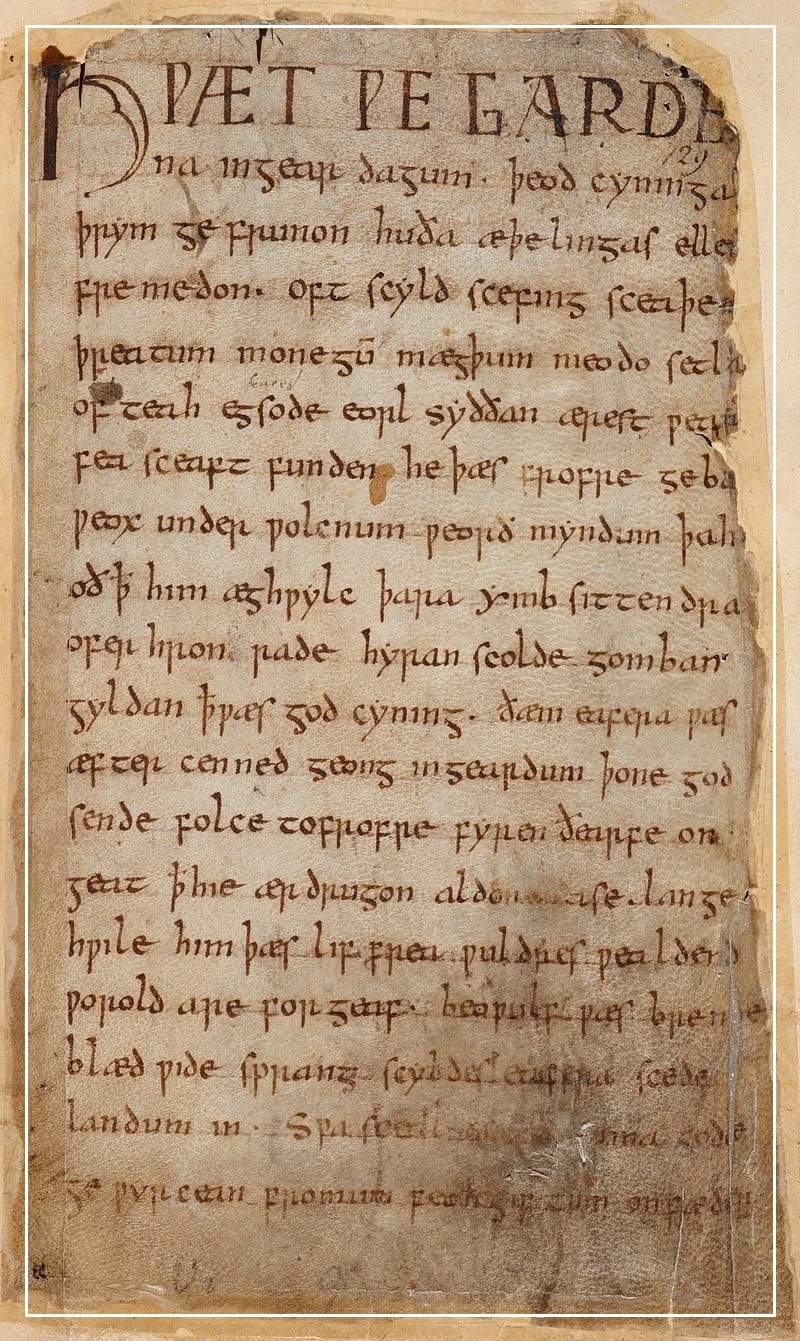

The use of monsters as analogs for some kind of minority representation, queer and disabled groups in particular, is not new. Look back to the earliest written text in the English language, Beowulf, to see this in action:

The image above is the first page of Beowulf's only surviving manuscript, written sometime between 975-1025 C.E. It is written in Old English and tells the story of the great hero Beowulf, come to aid the King of the Danes with his monster problem. Enter Grendel and his mother, described in the text as descendants of the Biblical Cain. Their monstrosity, in the medieval tradition, comes first from that heritage, their actions and behaviors reflecting a tainted lineage. By clearly associating the pair with the mark of Cain, the Beowulf author reinforces the idea that Grendel must always wander, that he is cursed already at birth. His mother, however, causes much greater consternation among audiences medieval and modern. As Grendel's mother, she possesses the same monstrous lineage as her son presumably, but as a woman, her behaviors of revenge-seeking and physical prowess against Beowulf further queer her in this gendered and hierarchical society. Over time, Grendel's mother has become a stand-in for the monstrous, as demonstrated by the ongoing debate surrounding her character. Wikipedia does a good job condensing the scholarly conversation and providing some sources to start with, if you're curious to read more.

All that to say, by the time we arrive in 2024, monster tropes have been well-established. New authors bring unique perspectives to established patterns, however, raising new questions of love, the body, perception, and usefulness. Ideas of trauma and familial abuse can naturally stem from these questions, and Wiswell also explores these possibilities throughout the text.

The text opens with the following, setting the stage for an empathetic reading of monstrosity, many of us have also been the monster:

Dedicated to everyone who has been made to feel monstrous

Shesheshen is a literal monster, a non-human being whose body is itself a liminal space, becoming whatever she needs it to be in that moment. But Homily, the human woman love interest, is also presented in the narrative as ambiguously monstrous. Fairly early on, the two women find themselves in a crowded pub. It is the monster who comments on societal definitions when she notices Homily alone and ostracized from the other humans, rows of empty tables between her and the rest of the crowded bar:

Nobody approached that barrier of empty tables, because they feared to go near her. They were treating her like she was monstrous.

She was not monstrous.

This was monstrous.

This early in the text, Homily's ostracization is presented without further explanation, simply that she is being clearly delineated as outcast. I admit, it was easy to read this moment through the queer experience; the two female characters had already been flirting, and I expect to find this kind of treatment frequently, having experienced it in real life and read it in nearly every book written by a well-meaning straight person. As in life, the reality of Homily's situation is far more complicated than that, but I think the imagery of this moment is quite intentional. Homily is queer and while a label is never in play, references to ex-girlfriends abound. But she is also significantly overweight, a description which took time for me to realize because of how lovingly Shesheshen describes Homily at all times. Fatness in the U.S.A based culture I was raised in carries additional labels of monstrosity, but by deemphasizing that aspect of Homily's description I believe Wiswell crafted her with genuine care.

Telling a love story through the eyes of an orphaned monster also made some really interesting resonances between other things I've read lately. In particular (I'll always find a way to link things back here), the Locked Tomb series and the questions of vampirism giving way to cannibalism/consumption as love clearly echo here. Wiswell's narrative is by no means the intricate and complicated craft Muir's is, but the themes and characters resonate. Some moments in this text which clearly evoke these questions include:

Observing the effect good music and dancing can have on humans, while managing to delineate Homily as Other: "No one offered Homily such Pseudo-cannibalistic harmony. Not until Shesheshen approached her."

And when Shesheshen must make herself look more human: "She forced herself not to digest some of this material. A couple of new lungs fitted her nicely, and a pancreas couldn’t hurt. If she was going to meet Homily’s mother and fit in with the humans, she needed an olfactory systems. Humans loved complaining about the smells of places. By sheer frequency of behavior, it was their second favorite thing, after going in private to defecate."

Which comes back in a hilarious moment a few pages later: "Having a nose made Shesheshen immediately feel more human, because it let her do what humans liked most: complain. [...] Of course there were humans with deaf noses, who were spared from the ritual of complaining about whatever they smelled. She wondered how often such people acted normal to avoid harm. She wished she’d studied them more, for her survival hinged on passing, and passing meant socializing."

However, even in these moments of brevity, there's a deeper conversation. Anyone with non-traditional gender expression or under the trans umbrella knows what an ambiguous and ever-changing gate the idea of passing creates. Shesheshen is not only trying to pass for human, but when an infant version choses its own gender near the end of the narrative, I realized Shesheshen also chose a gender for herself, one where the rules of passing are often elusive and weaponized. She never has to say in the text "I am a woman," the details are simply provided in this casual way. There's something profound for me in this; as a transgender man with some pretty non-confirmative ideas about masculinity, I struggle with questions of passing still, years after social and medical transition. This is what it means to have diverse characters, whose qualities just so happen to exist, and are not plot dependent (I'm still looking at you Russel T. Davies...).

All these elements add together to create a fairly strong story which I enjoyed a lot. However, it stands out as much more jarring when there are instances of outdated language used. In the same way most places have finally understood the microaggression of preferred pronouns, there are 2 instances wherein a character who appears at no other times is described as "an enby." When moments like these happen, my heart drops. This use reads as clunky, an attempt at performative inclusivity. Now, non-binary people are not a monolith, and plenty of people use enby to describe themselves. However, there are some issues with this as a catch-all term. While many see “enby” as an attempt to have a word such as “man” or “woman” to describe non-binary people, all that is happening is another umbrella word, a trichotomy instead of a dichotomy, implying Nonbinary is a category in opposition to more culturally accepted genders. Especially where the character doesn’t speak and isn’t named, it feels forced and grandstanding. I understand the good intentions here, but in 2024 I don’t have time for intentions anymore when perusal around large digital social communities can give insight into this conversation, and have for years now.

Overall, I really enjoyed the novel. Shesheshen and Homily are great characters dealing with their own traumas, which is what ultimately allows them to be together in the end. They help each other heal by accepting each other as they are, and while that leads to some formulaic moments of justice being served, Wiswell continues the narrative long enough to show the impacts of trauma, and what healing from PTSD can look like. I recommend the book overall, but especially for fans of queer romance and monster stories.

This Reminds Me:

- Cannibalisms/consumption as love

- Monstrosity as queer reading

- Martha Wells: Witch King

- Tamsyn Muir: The Locked Tomb series

- C.S.E. Cooney: Saint Death's Daughter

- Of reading all the vampire novels I could get my hands on in high school

- Hello Anne Rice

- Rin Chupeco: Silver Under Nightfall is better